Coursework

Four selected research projects of my graduate coursework.

Who benefits most from the Peruvian postsecondary educational system?

I used a large Peruvian household survey (n = 65.615) called ‘Encuesta nacional de hogares 2017’ (ENAHO) to investigate which education leads - on average - to the highest income. Under investigation were four levels of post-secondary education and eight different fields of study. Methodologically challenging was the fact that Peru has one of the biggest informal labour markets (non-registered work). Individuals working at own account usually do not report their income situation. Thus, I had to deal with high selectivity for income reports. I considered this bias by applying a Heckman-two-stage regression.

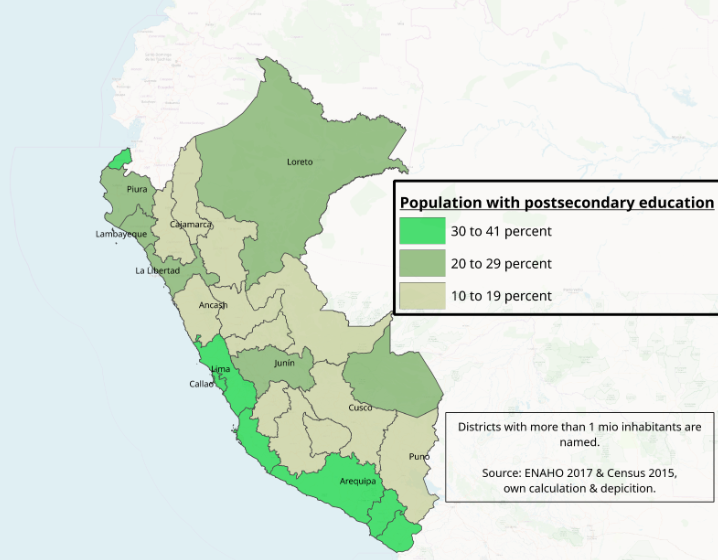

Figure 1 above shows, that only a relatively small fraction of the Peruvian population has postsecondary education (PSE). The more urban a district gets, the higher the share of inhabitants with PSE ranging from 13 % in Cajamarca and Apurimac to 41 % in the district of Lima.

Basic education (educación basica) is taught in “centros de educación técnico-productivo” (CETPRO), which are provided publicly as privately by about the same proportion. Graduates receive the title “auxiliar técnico”. Medium level education is provided by “institutos de educación superior tecnológico” (IEST). Graduates receive the title “técnico”. The majority of IEST institutions is private with about 70%. The “superior” level is called “educación superior non-universitaria”, non-university higher education. This level is also provided by IEST and other institutes in the fields of art, pedagogy and defence. The courses duration is between three and four years and leads to the title “profesional técnico”. The univseristy level is provided by about 140 universities from which about 65% are private. About 60%, or 900.000 students, of all postsecondary enrolments belong to universities.

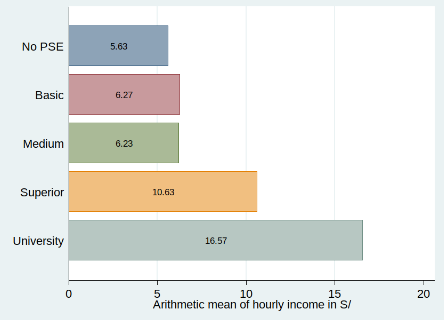

Figure 2 above shows the average income for employed Peruvians. The data show relatively low income differences for the first three levels of PSE with about 6 nuevo soles (S/), i. e. about 1.50 €. There might be two reasons for this finding. First, the demand for those graduates is very low and they have to compete with a majority of individuals without PSE. Second, the quality of basic and medium level institutes are often assessed as of poor quality which subsequently might lower human capital for their graduates. The findings indicate, that basic and medium level degrees might not be directly beneficial, but indirectly by elevating the probability of finding an occupation as employee which comes along with a higher income. Employed superior PSE graduates have a hourly mean income from 10.63 S/ (2.70 €). University graduates have the highest hourly mean income with 16.57 S/ (4.20 €).

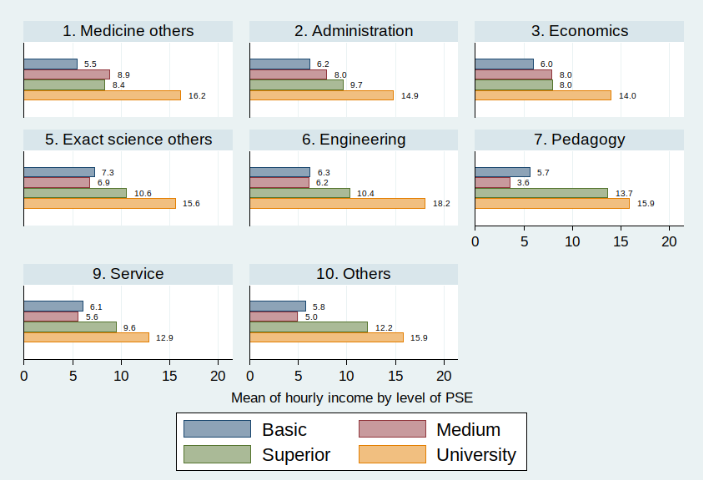

Concerning income differences between fields of study, my findings suggest that engineers (besides lawyers and physicians) benefit most at the university level. Even though, there is high demand in this field, engineers at the superior level only range in the upper half of income returns in comparison to other fields of study. Pedagogues have the highest income returns at the superior level and are the only ones which can - just like that - compete with incomes from university graduates. The field of administration only rises chances of higher incomes at the superior level. At the university level, graduates from the service field have the lowest income returns.

Refugee`s pre-migration, during flight and post-migration stressors and current psychological distress

In this assignment I investigated Syrian refugee`s pre-migration, during flight and post-migration stressors and its connectionn to psychological distress levels after resettlement in Germany. To do so, I enriched the “IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees in Germany” with spatial information concerning the Syrian civic war from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. This allowed me to investigate the influence of traumatic life events for a longer time span and compare them between each other.

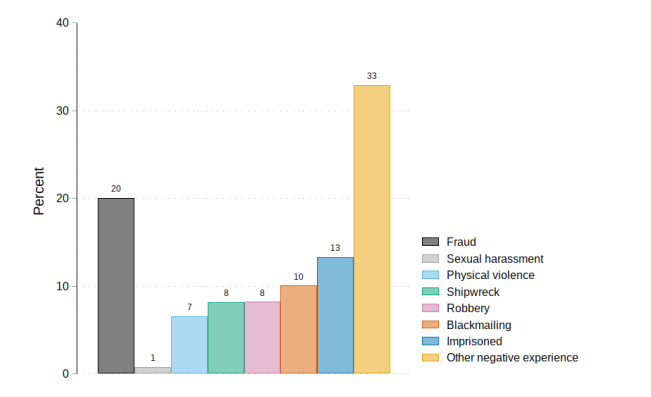

Figure 1 shows that about 70% made negative experiences during the flight. Besides “other negative experiences”, “fraud” was stated most often (20%), followed by “imprisoned”, stated by 13%. 8% of all Syrians refugees experienced a shipwreck.

Findings in figure 2 suggest, that pre-migration stressors, measured as the proportion of “people in need” in a specific Syrian district, still influence a refugee’s distress level, although there is no exposure to war and violence any more. The standardized effect, however, is only about 1/3 the size of negative experiences during the flight, and about 1/5 the size of the strongest impact on distress, seeking for family reunion. I assume, that high variation in my variable “people in need” (as it covers wide geographical areas) wrestled down the models significance calculations.

To put it in a nutshell, the data indicate that Syrian refugees suffer most and to a similar extend from family separation and from an unclear outcome of their asylum application, meaning from current, post-migration stressors. From this cross-sectional perspective, it seems, that the more time passes, the less affected individuals are from potentially traumatic experiences. However, longitudinal data which measure psychological distress levels at different time points would be needed, to investigate this assumption soundly. Note also, that this only holds for distress in general, and might presumably be different for pathologic distress levels, such as PTSD.

Chances and hazards of online platform workers in Europe

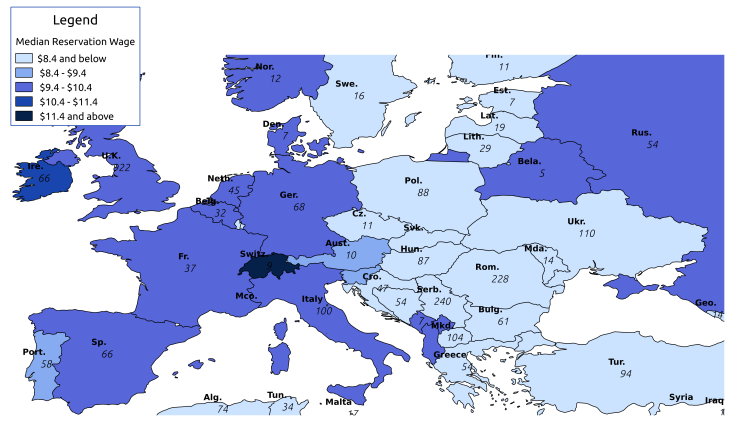

In this assignment I wanted to give a brief overview of European platform workers and their current regulatory situation. Moreover, I presented a data driven approach to assess the prevalence and inclusive potentials of this form of labour. Concerning the current state of empirical data on online platforms, scholars find that “relatively few empirical examinations of contemporary digital geographies” are available (Richardson, 2018, p. 246). Also political advisers report: “a crucial issue in designing the policy response to the emergence of digital labour platforms is the lack of reliable evidence.” (Pesole et al., 2018, p. 3). This finding is surprising, as data on platform work are - per definition - available on online platforms. Thus, I presented a data driven approach to investigate reservation wages (RWs) of web-based PWs across Europe on the platform guru.com. It provides low level geographical information of its PWs, their digital skills as well as their reservation wages. I focussed on the low-skill task “data entries”. This was due to two reasons. First, those tasks require very few skills and therefore have a higher inclusive potential for lower-educated individuals and second, the majority of web-based platform work consists of those types of task.

Figure 2 shows reservation wages across Europe as well as the number of PWs which provide data entry tasks on guru.com. First of all, the majority of data entry workers are not located in Europe. India has by far the most data entry workers with 129.984 cases on the platform, followed by the United States with 60.647 PWs. In line with the COLEEM survey, I find the highest incidence of low-skill PWs in the United Kingdom (n=2012), followed by Romania (n=405), Serbia (n=309) and Hungary (n=157). Reservation wages in East Europe are smaller than in West Europe. Nevertheless, potential earnings of $8 per hour for Romanian, Serbian and Hungarian PWs are much higher than their countries median gross hourly earnings of respective $2, $3 and $4 (Eurostat, 2016). Thus, it is not surprising, that the highest incidence of East European PWs on guru.com falls together with its poorest regions. This data driven investigation supports the assumption, that web-based online platforms can serve as a tool for labour market integration. Especially for young, less educated individuals from rural or disadvantaged regions with family responsibility.

Concerning the hazards of an unclear labour status, national and European legislatives seem to have a “’wait-and-see’ attitude” (De Stefano and Aloisi, 2018, p. 26). This might be due to the “embryonic phase” of this sector (ibid.). The instrument of lawsuits, from e.g. nationaltrade unions, only improves conditions of very particular PWs (De Stefano and Aloisi, 2018, p. 32). Until today, “[p]aradoxically, a courier performing the same activity can be classified as a quasi-subordinate worker in Italy, as a self-employed worker in France, as an employee in Germany, as a “zero-hours” contract worker in the UK or as an intermittent worker in Belgium. Definitely, a strong showing of fragmentation and weakness” (ibid., p. 53).

The nexus between income inequality and economic growth

In this course at the Max-Planck Institute for the Study of Society I investigated the nexus between income inequality and economic growth. I wrote an essay about the question, whether the causal relationship of rising inequality → stagnating demand from the middle class → hampered growth is supported empirically.

The connection between economic growth and functional/personal income inequality “seems to be complex and heterogeneous” (Anselmann, 2020, p. 247). However, current research suggests that when there is a relationship between inequality and growth, it is not characterized by a “trade-off” as stated by Okun (1975). To get a better understanding of which mechanisms might work “behind the scenes”, I discussed an explanatory approach by Baccaro and Pontusson (2016). They see inequality as a consequence of a specific growth model.

Baccaro and Pontusson argue that the wage share in Germany did not rise in the last two decades because of Germany’s dependency on exports (export-led growth model). They argue that strong price sensitivity of German exports in manufacturing allowed companies to restrain wages. Labour unions in Germany even supported these wage restrains in favour of risking job cuts. Furthermore, a rising wage share may induce rising domestic prices which upgrades the domestic currency. Thus, rising wages would hamper the German economy twofold: i) by increasing production costs due to higher labour costs and ii) by stressing foreign demand due to a currency appreciation:

"To the extent that exports are price-sensitive, growing exports requires repression of wages and consumption to prevent an appreciation of the real effective exchange rate" (Baccaro and Pontusson, 2016, p. 189; see also Behringer et al., 2016, p. 9).

They argue, that income inequality at the bottom of the income distribution in the three other investigated countries (Sweden, UK and Italy) did not rise as strong as in Germany because i) their economies rely stronger on domestic demand and ii) their exports are much less price sensitive. However, Baccaro and Pontusson leave two points unaddressed. First, within their argumentation line they do not provide evidence for their precondition that German exports are more price-sensitive than those from the UK and Sweden. As Sauer (2018) shows, German export products - at least still - can be characterized as “price-making” products. One reason for this is the high prestige German products have in exporting regions like Asia. The other reason is that industrial investment goods such as automation technology are lacking concurrency. The second point is that they do not work out the mechanisms they actually want to address. They state

"the key difference between Germany and Sweden is, we believe, that German export firms, by virtue of the price sensitivity of their products, were less willing to concede to the wage claims of their own employees and also pushed much harder than Swedish export firms to ensure that wage increases in the export sector would not spill over into economywide increases in labor costs. In this effort, they were aided by the weakness of service-sector unions or, in other words, the dominance of export-sector unions within the German labor movement."

How “German export firms” have the power to “ensure that wage increases” do not “spill over” into other sectors remains open. Also, how “the dominance of export-sector unions” is connected to the low-wage service sector. The authors, however, recognize that institutional factors such as changes in labour protection and the rise of “Atypische Beschäftigung” allowed companies to further decrease wages at the lower end (ibid., p. 196). Whether or not labour market deregulation affected the German growth, remains unsolved. Achim Truger (2019), for example, disagrees with the assumption that the institutional expansion of low-wage occupations supported Germany’s growth rates. The liberation of labour regulations may not have contributed to the German growth in the last decade: Germany in comparison to other countries still has relatively labour supportive market regulation policies. Following the argumentation of Baccaro and Pontusson, the introduction of the minimum wage should have had a negative impact on Germany’s international and domestic competitiveness, but no negative consequences emerged whatsoever.

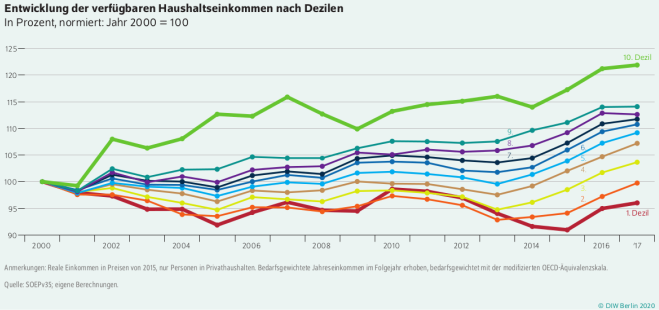

When wage negotiations in the manufacturing sector are not directly linked to the wage development in the service sector the question remains open, what mechanisms hold back incomes in this sector to rise. From a naive Kaleckian perspective, when the middle class enjoys rising wages, this should also lead to an increase in consumption, i.e. rising demand for gastronomy, tourism and other “low skill” services. However, figure 1 shows that these incomes remain decoupled from this upswing as the incomes of the lower 20% even decreased between 2000 and 2015. First after 2015 incomes of the lowest decile rose again, after the introduction of a minimum wage (Grabka and Goebel, 2020, p. 318). Grabka and Goebel show that differentiating between migrants and native low-wage earners may also give hints which mechanisms might be at work. They show that the share of native low-wage employed among all employed natives declined slightly between 2011 and 2017 (≈ 12.5%), whereas it rose steadily for individuals with a migration background (from 23% to 30%). As pointed out by Cingano (2014, p. 6), education may mediate the mechanism between (low) incomes and growth. As individuals with a migration background have - by means - a lower level of education, this could be both, a cause of inequality and of hampered growth. Baumol’s cost disease theory (see Hartwig and Krämer, 2018, p. 3), which appreciates the fact that technological change - and thus productivity increases - affects manufacturing much stronger than service labour, may also help to explain why wages did not increase in the German service sector. However, it gives no explanation, why they even fell in times of growth.